Domikus Böhm’s Heilig-Kreuz Kirche in Dülmen

The Romanesque Facade of the Abbey Church in Heiligenkreuz

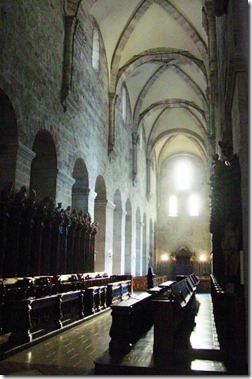

The Romanesque Facade of the Abbey Church in Heiligenkreuz

In a fascinating series Shawn Tribe and Matthew Alderman, have been examining what they call “The Other Modern” in sacred architecture: architecture which learns from the tradition rather than rejecting it, but which nevertheless has a peculiarly modernist flair. One of the questions which they have raised is whether it is possible to make use of elements of modernist minimalism and austerity in an authentically Catholic fashion. Even if the avante garde of modernism tended to use minimalism as an expression of nihilism, or the as a revolutionary demonstration of man’s self-alienation in his works, are there no other uses possible? Could one use a form of modernist austerity to achieve “noble simplicity”? There have certainly been architects who thought that it could, and the “Other Modern” series has brought some interesting examples to light. There have, after all, been examples of austere architecture in the Church’s past, Tribe and Alderman raise the example of Cistercian architecture.

The question of modernist vs. Cistercian austerity came to my mind last summer when I took a tour of the Heilig-Kreuz Kirche in Dülmen, built by the German architect, vestment designer, and composer Dominikus Böhm. Now, Böhm’s architecture is not an example of the “Other Modern”–it is simply modern–but I think a consideration of it can help to show what it is about modern austerity that a successful Other Modern has to avoid. Böhm was an enthusiastic proponent of the twentieth century Liturgical Movement, and, while a convinced modernist, he included allusions to traditional architectural styles – especially the Romanesque – in his buildings for the sake of better expressing his theology. The tour guide, who lead some of my confreres and me through the Church, made a point of comparing Böhm’s architecture in general with Cistercian architecture, and Dülmen in particular with our Abbey Church in Heiligenkreuz, which has some striking coincidental similarities to Heilig-Kreuz Dülmen.

This has set me thinking on what exactly the meaning of austerity was for the Cistercian Fathers, and how it relates to the turn to austerity in the ecclesiastical architects of the industrial age, especially those associated with the Liturgical Movement. For S. Bernard austerity in architecture was part of monastic perfection. In the Apology to William S. Bernard writes the following:

I say nothing of the enormous height, extravagant length and unnecessary width of the churches, of their costly polishings and curious paintings which catch the worshipper’s eye and dry up his devotion, things which seem to me in some sense a revival of ancient Jewish rites. Let these things pass, let us say they are all to the honor of God. Nevertheless […] I as a monk ask my fellow monks: […] “Tell me, poor men, if you really are poor what is gold doing in the sanctuary?” There is no comparison here between bishops and monks. We know that the bishops, debtors to both the wise and unwise, use material beauty to arouse the devotion of a carnal people because they cannot do so by spiritual means. But we who have now come out of that people, we who have left the precious and lovely things of the world for Christ, we who, in order to win Christ, have reckoned all beautiful, sweet-smelling, fine-sounding, smooth-feeling, good-tasting things– in short, all bodily delights–as so much dung, what do we expect to get out of them? (S. Bernard, Apologia ad Guillelmum abbatem)

The contrast that he makes to cathedral churches is illuminating. He is willing to grant that for the “fleshly people” lavish decoration can be a means to arousing devotion; for them it is a good thing that leads them to God, but it is not fitting to monks. For S. Bernard not all ways to God are equal, and the monk is supposed to try to follow the most perfect way. One can compare S. Bernard’s teaching on marriage to his teaching on art. Marriage is a good thing and a way to God, but it is not the most perfect way to God— virginity is a more perfect way. Similarly, lavish art is a good thing, which can arouse devotion, but it is more perfect to do without it. The monks are called to give up all consolations of the senses, to concentrate entirely on the unum necessarium.

Now compare the passage from S. Bernard with one from a biography of the controversial twentieth century Catholic craftsman and sculptor Eric Gill:

[Gill’s] concern to root out the fake in art led him to praise machine-made reinforced buildings, without however deviating from his belief that ‘Industrialization whatever the grandeur of its products is ultimately incompatible with the nature of man’. His own experience in an architects office had been of providing scale drawing of fake Gothic ornaments. and once for both sides of a wrought iron gate! No wonder then that he […] said it was more honest to be true to our machine society and to make buildings, furniture and utensils that are un-adorned, functional and true to their materials. ‘Plainness is a negative virtue, it is a privation, an asceticism’. (Malcolm Yorke, Eric Gill: Man of Flesh and Spirit, p. 93)

Gill had a great love of ornamentation, and he saw austerity as an unfortunate necessity forced on man by the Industrial Revolution, which had turned ornamentation into kitsch. In his essay “Twopence Plain, Penny Coloured” he argues that plainness is a necessity of the moment to wean the people of bad taste, but that (once the distributist-agrarian movement has succeeded) it will be time to return to the ornate. For Gill the austere is inferior to the ornate, but unfortunately necessary in our degraded circumstances. That is nearly the opposite of S. Bernard’s teaching; S. Bernard thinks the ornate is inferior, but may be justified for the sake of those who are not willing to chose the way of perfection. But despite this opposition between S. Bernard’s and Gill’s positions, I think that architects like Böhm combine aspects of both. Let us take a look at the Heilig-Kreuz Kirche in Dülmen, comparing and contrasting it to Heiligenkreuz.

The massive stone exterior makes obvious references to the Romanesque, but it is free of all ornament save for a huge rose window, designed by Böhm.

The Rose Window in Dülmen

The Western Windows in Heiligenkreuz

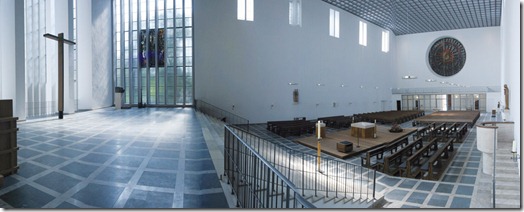

The interior is shaped like a big rectangular box, with a flat ceiling supported by steel rafters. The nave is very dark with only small widows near the ceiling.

The Nave towads the West in Dülmen

The Nave towads the West in Heiligenkreuz

The darkness of the nave stands in intentional contrast to the light which floods into the church from hidden windows behind the sanctuary, which is raised unusually high. By coincidence, this leads to a similar effect to that caused in the Abbey Church in Heiligenkreuz, by the joining of the dark, Romanesque nave to a huge Gothic sanctuary whose windows let in a blaze of glory, signifying the heavenly Jerusalem.

Interior toward the East in Dülmen

Interior toward the East in Heiligenkreuz

Interior at Dülmen toward the South

Sanctuary at Heiligenkreuz

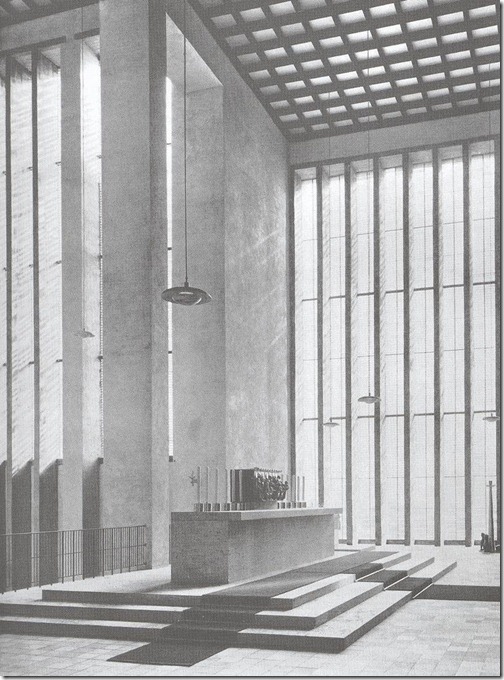

The theological idea behind Böhm’s use of light was deeply rooted in the Liturgical Movement of his day. The dark nave signifies the human condition in the darkness of sin. Today the altar has been taken out of the sanctuary and placed at the front of the nave, but originally the altar was not only up on the high platform of the sanctuary, but it was farther raised by three steps. All eyes where to be drawn to the sacred sacrifice taking place on the altar. On the altar was a tabernacle with a relief of the Last Supper. The light flooding in from behind made the altar and tabernacle appear as a black silhouette. This gives a picture of all of salvation history; man is saved from the darkness of sin by passing through the death of the cross into the glory of the Resurrection. Behind the sanctuary the floor falls again to the level of the nave, forming a kind of chapel where the 19th century mystic Bl. Anna Katharina Emmerick is buried. From the nave one can see neither the floor of the Emmerick chapel, nor the windows at its sides, giving a remarkable impression of an infinite realm of light.

The Sanctuary in Dülmen in 1939

Dominikus Böhm’s Tabernacle, showing the Last Supper

Dominikus Böhm’s Tabernacle, showing the Last Supper

Dominikus Böhm’s Sanctuary Lamp

At first it seems that Böhm uses austere simplicity for reasons very close to S. Bernard. He wanted a complete lack of distraction, a complete concentration on the mystery of salvation that is made present on the altar. But Böhm does not see this austerity as tied to a particularly state in life—he wants it for all Christians. There is a kind of one-size-fits-all attitude to the 20th century Liturgical Movement, that is probably tied to modern egalitarianism, and perhaps also to attitude toward human life fostered by industrialism. And it is its roots in the industrial that is perhaps the chief aesthetic difference between Böhm’s architecture and Cistercian Romanesque. The huge expanses of featureless steel, glass, and concrete which Böhm uses have the kind of machine-like quality, which Gill thought of as the most honest way of building in our age. But this machine-aesthetic is very different from the Cistercian aesthetic. The Cistercian Romanesque is ordered to withdrawing from the beauties of the visible world to seek God alone, but it does not deny those beauties. Even in its plainness, Cistercian architecture has a human quality; the proportions, the workmanship, the few ornamental details—they all speak of a basically friendly world, one which it is a real sacrifice to give up. The machine aesthetic has a kind of Manichean contempt for the material world; its featureless expanses of industrial perfection speak of a world which is basically alien to man. Far from showing the visible as a world of sensible delight, from which one withdraws into the desert to be alone with God, it tries to de-mask the world as a basically ugly, strange place, in which there is no danger of our feeling at home anyway. Böhm does achieve a certain grandeur, but it is a grandeur (to quote Gill again) ‘ultimately incompatible with the nature of man’. For the “Other Modern” Böhm’s industrial austerity can serve as an example of what to avoid.

Windows in the South wall of the Sanctuary at Dülmen

Photo Credits: here; here; here; and in Holgar Brühl’s brilliant article, “Architektur, Macht und Übermacht. Thesen zur Architektur Dominikus Böhms in den 1930er Jahren,” in: Münster 58.1 (2005) pp. 45-52, at p. 47.

Leave a comment