In his weird and partly brilliant book on infinity, David Foster Wallace writes, “what the modern world’s about, what it is, is science.” That is, the heart of the modernity as a project is the new science developed in the 17th century, which consists in the application of a certain kind of symbolic-calculation to nature through experiments for the sake of technological power over nature. This science was “new” because unlike the old science its goal was not the contemplation of the truth in the forms of things; the goal of the new science was and is practical. As El Mono Liso recently noted, “the attempt to analyze the world as a series of mathematical equations or chemical formulas is ultimately not an unbiased analysis of static essences, but a blueprint by which civilized actors seek to bend all things to their own will, in our case, the will of capital.” The reference to capital is crucial. The new science was wedded to a new attitude toward external wealth: capitalism. For the first for the first time in history “the economy” emerged as self-regulating system aimed at the measureless increase of exchange value. And it was capitalism that provided the main measure of the growth of technological power. Unlimited technological progress is the engine of economic growth, and unlimited economic growth the measure of technological progress.

The domination of nature through science was supposed to make man free. But, as Max Weber famously noted, it really enclosed him in an “iron cage,” subordinate to the system. It destroyed all his traditional bonds to the earth and his fellow men, and made even his eternal salvation seem trivial in comparison to the imperatives of the economy. The project of domination of nature through science was the basis of the ideology of progress, which initially took on a religious character, explicitly supplanting hope in Christ with hope in progress (as Pope Benedict XVI put it in Spe Salvi 17). As Owen White pointed out in recent comments on this blog, the ideology of progress no-longer retains its original form— it has lost some of its religious aura and has become more the necessary optimism of a business enterprise. But the fact remains that our world continues to be run on the presupposition that technological progress and economic growth are the most important goals, and that even if there is no guarantee that the project will end well, progress is still, in President Obama’s words, “the hope of all the world.”

Weber argued that this was the force driving the “secularization” of the world, and the popes have agreed with him. On February 22nd, 2013, after Pope Benedict XVI had announced his abdication, but before the vacancy of the Apostolic See had begun, I posted a reflection on the papacy and the false gospel of progress. I argued that one of the main concerns of the papacy, especially since the French Revolution, has been combating the program of progress. I argued further, though, that Vatican II tried a subtle strategy of modifying the idea of progress and subverting it to serve the gospel. And I ended by expressing something of a hope that this strategy would change again in the coming years:

One wonders how the strategy of the Holy See will developed in the coming decades. One can’t honestly say that the Council’s strategy was an unqualified success. Given the increasing hostility of a modern world which is ever more committed to violations of the natural law under the names of “reproductive rights,” “gay-rights,” “gender mainstreaming,” “the right to die,” and so on, one wonders whether future Popes will not return to a strategy more similar to that of Bl. Pius IX, who simply condemned the following proposition: “The Roman Pontiff can, and ought to, reconcile himself, and come to terms with progress, liberalism and modern civilization.”

I was hoping that Pope Benedict’s successor would be a new Bl. Pius IX. In many ways, of course, this hope was disappointed. Pope Francis certainly sees it as his task to continue the path marked out by the Council. But with the publication of Laudato Si’ part of my hope of February 2013 has been realized in a surprising way. Laudato Si’ strikes blow after blow with extraordinary passion and insistence against the technocratic-utilitarian heart of the modern project. As Rusty Reno at First Things has written, “this is perhaps the most anti-modern encyclical since the Syllabus of Errors […] Francis has penned a cri de coeur, a dark reflection on the systemic evils of modernity.” Reno means this as a criticism, but I take it as high praise.

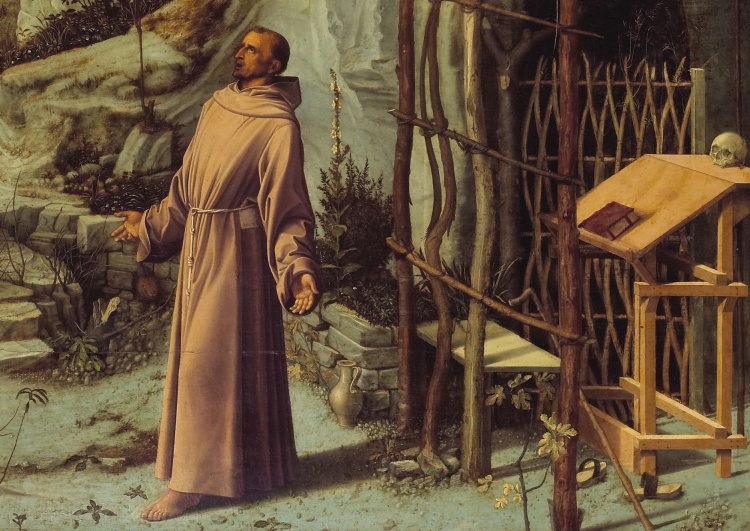

Pope Francis has indeed penned a cri de coeur against the destruction of God’s beautiful creation, the marring of the creatures whom God has given as so many words revealing his beauty and love, and the impoverishment and debasement of man, the destruction of human culture, and the oppression of the poor and murder of the innocent that have been the price of “progress.” But Laudato Si’ is much more than a cry of protest against the evils of modernity. What makes this a truly great and moving and beautiful encyclical is the magnificent exposition of another view of reality: a description of the true nature of the created order, in all its marvelous and interconnected glory, and of the true rôle of man as the gardener of this garden of wonders. Pope Francis’s style can at times be a tad bit rambling and prolix, and he lacks the incisive and subtle intellectual argumentation of Pope Benedict’s writings, but the shear wonder and love that suffuse Laudato Si’ makes this work of his rise to a very high level. He returns again and again to the wonder that filled his namesake, St. Francis:

Just as happens when we fall in love with someone, whenever [St. Francis] would gaze at the sun, the moon or the smallest of animals, he burst into song, drawing all other creatures into his praise. He communed with all creation, even preaching to the flowers, inviting them “to praise the Lord, just as if they were endowed with reason”. […] Saint Francis, faithful to Scripture, invites us to see nature as a magnificent book in which God speaks to us and grants us a glimpse of his infinite beauty and goodness. “Through the greatness and the beauty of creatures one comes to know by analogy their maker” (Wis 13:5); indeed, “his eternal power and divinity have been made known through his works since the creation of the world” (Rom 1:20). For this reason, Francis asked that part of the friary garden always be left untouched, so that wild flowers and herbs could grow there, and those who saw them could raise their minds to God, the Creator of such beauty. Rather than a problem to be solved, the world is a joyful mystery to be contemplated with gladness and praise. (11)

And he turns to look at our Lord from Whom St. Francis learned this attitude:

In talking with his disciples, Jesus would invite them to recognize the paternal relationship God has with all his creatures. With moving tenderness he would remind them that each one of them is important in God’s eyes: “Are not five sparrows sold for two pennies? And not one of them is forgotten before God” (Lk 12:6). “Look at the birds of the air: they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them” (Mt 6:26). […] As he made his way throughout the land, he often stopped to contemplate the beauty sown by his Father […] Jesus lived in full harmony with creation, and others were amazed: “What sort of man is this, that even the winds and the sea obey him?” (Mt 8:27). […] The New Testament does not only tell us of the earthly Jesus and his tangible and loving relationship with the world. It also shows him risen and glorious, present throughout creation by his universal Lordship: “For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, making peace by the blood of his cross” (Col 1:19-20). This leads us to direct our gaze to the end of time, when the Son will deliver all things to the Father, so that “God may be everything to every one” (1 Cor 15:28). Thus, the creatures of this world no longer appear to us under merely natural guise because the risen One is mysteriously holding them to himself and directing them towards fullness as their end. The very flowers of the field and the birds which his human eyes contemplated and admired are now imbued with his radiant presence. (96-100)

One of the most brilliant things about the encyclical is how it shows that our Lord’s love of creation was explicated in St. Thomas Aquinas’s theology and philosophy of nature. He summarizes St. Thomas’s argument, which is so dear to my own heart, that the multiplicity and order of creation is the manifestation of the divine glory:

The universe as a whole, in all its manifold relationships, shows forth the inexhaustible riches of God. Saint Thomas Aquinas wisely noted that multiplicity and variety “come from the intention of the first agent” who willed that “what was wanting to one in the representation of the divine goodness might be supplied by another”, inasmuch as God’s goodness “could not be represented fittingly by any one creature”. Hence we need to grasp the variety of things in their multiple relationships. We understand better the importance and meaning of each creature if we contemplate it within the entirety of God’s plan. As the Catechism teaches: “God wills the interdependence of creatures. The sun and the moon, the cedar and the little flower, the eagle and the sparrow: the spectacle of their countless diversities and inequalities tells us that no creature is self-sufficient. Creatures exist only in dependence on each other, to complete each other, in the service of each other”. (86)

And he even quotes my favorite text from St. Thomas’s vital commentary on Aristotle’s Physics, on the nature of nature:

God is intimately present to each being, without impinging on the autonomy of his creature, and this gives rise to the rightful autonomy of earthly affairs. His divine presence, which ensures the subsistence and growth of each being, “continues the work of creation”. The Spirit of God has filled the universe with possibilities and therefore, from the very heart of things, something new can always emerge: “Nature is nothing other than a certain kind of art, namely God’s art, impressed upon things, whereby those things are moved to a determinate end. It is as if a shipbuilder were able to give timbers the wherewithal to move themselves to take the form of a ship”. (80)

The Aristotelian understanding of nature as an internal principle of motion and rest ordered to a determinate end, as perfected by St. Thomas, is radically opposed to the instrumental understanding of nature in the Baconian/Cartesian project. I think it is one of, or perhaps the, most important intellectual tasks of our day to recover the Thomistic understanding of nature.

It is from the perspective of his rich reflection on the true nature of creation that Pope Francis criticizes the modern project:

It can be said that many problems of today’s world stem from the tendency, at times unconscious, to make the method and aims of science and technology an epistemological paradigm which shapes the lives of individuals and the workings of society. The effects of imposing this model on reality as a whole, human and social, are seen in the deterioration of the environment, but this is just one sign of a reductionism which affects every aspect of human and social life. We have to accept that technological products are not neutral, for they create a framework which ends up conditioning lifestyles and shaping social possibilities along the lines dictated by the interests of certain powerful groups. Decisions which may seem purely instrumental are in reality decisions about the kind of society we want to build. (107)

And it is this background that gives weight to his cri de coeur:

We have come to see ourselves as [sister earth’s] lords and masters, entitled to plunder her at will. The violence present in our hearts, wounded by sin, is also reflected in the symptoms of sickness evident in the soil, in the water, in the air and in all forms of life. This is why the earth herself, burdened and laid waste, is among the most abandoned and maltreated of our poor; she “groans in travail” (Rom 8:22). We have forgotten that we ourselves are dust of the earth (cf. Gen 2:7); our very bodies are made up of her elements, we breathe her air and we receive life and refreshment from her waters. (2)

One of the most helpful things about the encyclical is how Pope Francis shows that human society is a part of the order of creation, and depends on it. He shows how the false, technocratic view of nature is connected to a false technocratic liberalism in politics and society, which ignores and violates the natural law written in our hearts (155), aborts children (120), and destroys cultural tradition (145-146).

So is Pope Francis a new Pius IX? Not exactly. As Reno insightfully remarks:

Perhaps, therefore, the most accurate thing to say is that Francis offers a postmodern reading of Gaudium et Spes and Vatican II’s desire to be open to the modern world. He seems to propose to link the Catholic Church with a pessimistic post-humanist Western sentiment rather than the older, confident humanism.

In our contemporary moment, which is both postmodern and hypermodern, it is fashionable to oppose capitalism in word and symbol while promoting it in fact. There indeed a strain of pessimistic anti-modernism abroad today. Former Vice President Al Gore’s critique of Cartesian rationalism is strikingly similar to Pope Francis’s:

The Cartesian approach to the human story allows us to believe that we are separate from the earth, entitled to view it as nothing more than an inanimate collection of resources that we can exploit however we like; and this fundamental misperception has led us to our current crisis […] We have assumed that our lives need have no real connection to the natural world, that our minds are separate from our bodies, and that as disembodied intellects we can manipulate the world in any way we choose. Precisely because we feel no connection to the physical world, we trivialize the consequences of our actions. And because this linkage seems abstract, we are slow to understand what it means to destroy those parts of the environment that are crucial to our survival. We are, in effect, bulldozing the Gardens of Eden. (Earth in the Balance, pp. 218 and 144).

Pope Francis’s encyclical is meant in part to appeal to such persons as Gore, and persuade them that the evils of Cartesian rationalism are not best fought by promoting contraception and abortion in the Third World, but by conversion to God, and true love for all of his creatures. So Reno seems to be right; Pope Francis does seems to be continuing the Vatican II project, but in a different context.

As an integralist I think that Pope Francis ignores some elements of Catholic social teaching that ought really to follow from his own position on human society as a part of the order of creation, and his rejection of technocratic liberalism. I think that some of his actions, and his evident contempt for “traditionalism” in the Church, are not really consistent with his vision. But at the moment I am just grateful for this magnificent gift.

In one of the better responses to the encyclical, Chad Pecknold writes, Laudato Si’ “could have been written by J.R.R. Tolkien.” I can see what he means. When I read it I was most reminded of a thinker who was deeply influenced by Tolkien: Stratford Caldecott. Stratt’s final book, Not as the World Gives, reads like a commentary avant la lettre on Laudato Si’. It is filled with the same wonder and joy at creation, the same horror and sadness at its marring, the same devotion to St. Francis. And it gives the same vision of a beautiful order that ought to encompass all creation: stars and trees, birds and donkeys, human persons, cultures, and societies.

Leave a comment