A while ago I posted a response to an First Things essay by Roger Scruton on the good of government. I later sent an abridgment of my post to First Things as a letter to the editor. It appeared in the October issue, with the following reply by Scruton:

As for Fr. Waldstein’s theological vision of the good of government, I can only respond as Burke responded to the Reason advocated by the French Revolutionaries. He wrote: “We are afraid to put men to live and trade each on his own private stock of reason; because we suspect that this stock in each man is small, and that the individuals would do better to avail themselves of the general bank and capital of nations and of ages.”

Advocates of natural law in the Catholic tradition have often told us that the good is discoverable to reason, and that we have only to consult it. But they tend to be as reluctant as Waldstein to define who is doing the consulting, and how. Burke’s view, that there is a kind of reason that emerges through civil association, and which is both conserved in our traditions and irretrievably dispersed by the attempt to make it explicit, offers, to my mind, a better model of the place of reason in government. On Burke’s view, rational solutions emerge from below, by an invisible hand, and are not imposed from above by those who claim to have privileged knowledge of the natural law. (The same point is made in other terms by Hayek, in his defense of the common law.) One can agree with Kant’s warning against paternal government without thinking that “any submission to an authority other than the self is tyrannical.” As I understand it, the art of living in society is precisely the art of submitting to authority—but doing so willingly, and in the little platoons that we ourselves create.

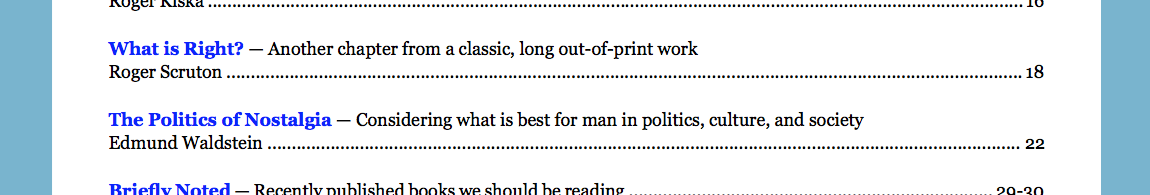

I have the greatest respect for Scruton, and certainly his position is not as bad Kant’s, but I’m still not convinced. He returns my Kant comparison with interest by comparing me to the Jacobins. But I was a little surprised by his saying that am “reluctant” to define who is to determine what the natural law is. True, I gave no account of that in my letter, but in the past I do not think I have been notably reluctant. By coincidence the most recent issue of The European Conservative features an excerpt from one of Scruton’s books and a notably unhesitant essay by me right next to each other in the Table of Contents:

On seeing this Coëmgenus noted the juxtaposition of Scruton’s title “What is Right” and my subtitle “what is best”—an illustration of two different approaches.

Leave a comment